At the lowest point in his life, the wrestler popularly known as "The Iron Sheik" tucked a razorblade into his cheek and walked into a Jonesboro, Ga., courtroom.

He was going to cut a man’s throat, and he had good reason to do so.

From the gallery, The Sheik—the real-life Hossein Khosrow Vaziri—narrowed his eyes and contemplated 38-year-old Charles Warren Reynolds, who rose nervously from the defendant’s table. When the judge asked him to address the court, Reynolds broke into tears and apologized for the murder of The Sheik’s 27-year-old daughter, Marissa.

With their mixed Iranian, German and Scandinavian ancestry, Marissa and her sisters, Tanya and Nikki, were striking. But The Sheik had also raised his daughters to be tough. In their Fayetteville, Ga., home, outside Atlanta, the Vaziri girls, along with a group of other kids from the neighborhood, endured a rigorous regimen of calisthenics and exercise.

As their father, a one-time World Wrestling Federation (currently World Wrestling Entertainment, or WWE) champion, stood over them, the sisters would lock up, push and pull on one another and go for single- and double-leg takedowns, the way The Sheik did when he trained in his native Iran.

“We do Greco-Roman, freestyle,” he says of the wrestling practiced in the family’s living room. “The Old Country way. No gimmick wrestling in my house.”

He also told his daughters that he’d always be there to protect them.

But in May 2003, as The Sheik recovered from knee replacement surgery, Marissa was partying in the apartment she shared with Reynolds. They argued slightly, but not to the degree that any of their guests were alarmed. When everyone left, Reynolds strangled Marissa, then pulled the blanket up to her chin, like she was asleep.

“She’s such a good girl,” Reynolds would tell police, “but she wouldn’t calm down.”

In court, The Sheik’s Minnesota-born wife, Caryl, warned the rest of the family about her husband’s homicidal intentions. Despite his recent surgery, The Sheik was strong and skilled enough to barrel through a court officer or two, spit out the blade and draw some blood.

So the entire clan surrounded the former bodyguard for the Shah of Iran, boxing him in near the wall, and refused to allow him to carry out his plan.

“You can’t kill him ‘cause they’ll put you in prison,” Tanya whispered. “I lost my sister and I don’t want to lose my father.”

Apparently touched by the words, The Sheik maintained his composure. And, as a tribute to Marissa, he made a pledge that he hoped would strengthen the family. He was going to quit drugs, particularly crack, a vice that gripped him as his professional wrestling career—and his funds—waned.

“The drug thing was so embarrassing,” says Tanya, “especially to someone who was an extreme athlete most of his life.”

KHOSROW OF THE IMMORTAL SOUL

The Sheik isn’t exactly sure when he was born. Although his passport reads March 15, 1942, he celebrates his birthday on Sept. 9. He blames the confusion on the fact that his family alternated between the Western calendar and the Solar Hijri calendar used in Iran and Afghanistan.

Throughout his childhood, he was called "Khosrow," for the Persian king known as “Khosrow the Just” and “Khosrow of the Immortal Soul.”

In his hometown of Damghan, there were no drugstores, so the elderly would occasionally relieve their ailments by smoking opium. Later, when the family relocated to Tehran, he looked through the windows of restaurants and bars and saw customers sipping beer. But he was neither curious about these diversions nor interested in sampling them himself.

By high school, he had one goal: wrestling at a competitive weight of 90 kilograms, or 200 pounds. To achieve this, for 40 weeks in a row, he traveled an hour-and-a-half to a special mosque where he asked Allah to intercede.

He also got "90" tattooed on his right forearm, the only mark on his body except for the Islamic crescent he’d add in the United States. Since there were no tattoo parlors in Iran, he went to a brothel and paid a prostitute to ink his flesh.

But that was the extent of the exchange. Because of his devotion to his sport, and strict Shiite beliefs, he did not lose his virginity until a visit to Germany, when he was nearly 29.

Contrary to the oft-repeated claim, The Sheik never competed in the Olympics—although he represented Iran in numerous international tournaments and was an assistant coach for the American Olympic team in 1972 and 1976. After relocating to Minnesota, The Sheik remained dedicated to amateur wrestling, winning silver medals in AAU Greco-Roman tournaments in 1969 and 1970 and the gold in 1971.

He’d take these medals everywhere—waving them around on television as a wrestling heel, or villain—until they were stolen, during his World Wrestling Federation days, from a Newark, N.J., hotel room he was sharing with tag team partner Nikolai Volkoff.

ONE OF US

It was in Minnesota that Khosrow Vaziri took the first step to becoming The Iron Sheik, training for professional wrestling with Verne Gagne, an NCAA champion and perennial titlist for the promotion he ran out of Minneapolis, the American Wrestling Association (AWA).

For extra money, The Sheik worked for Remus Roofing, owned by the father of future in-ring rival Sgt. Slaughter.

Initially, The Sheik believed that professional wrestling matches were legitimate contests. Then, after one session in the University of Minnesota’s wrestling room, Gagne smartened up his student to the industry’s most cherished secret: Although the participants were tough and proud, they worked together to entertain the public.

The newcomer didn’t like what he heard. “This is my sport,” he asserted. “I cannot be phony.”

But the promoter convinced The Sheik that he’d be joining the most exclusive of sports fraternities. “Be one of us,” Gagne pled.

The Sheik agreed, with mild trepidation. But once he compromised, other concessions followed. When fellow wrestler Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka offered him a joint, The Sheik acquiesced.

It was a door that he sometimes wished he’d never opened. After a cloistered lifetime centered around athletics, The Sheik became such a prolific substance abuser that his road tales still circulate through wrestling dressing rooms.

There was the drunken night when he grabbed “Mad Dog” Buzz Sawyer in their hotel room and gave him a belly-to-belly suplex through the bed. While waiting at customs to enter Canada, he unzipped the bag in front of him and stashed his cocaine in the sweatshirt hood of “The Berserker” John Nord, resulting in one of The Sheik’s numerous dismissals from the World Wrestling Federation.

Just prior to another termination, he was told that he’d failed a drug test. The Sheik replied by naming several other stars and asking his boss, Vince McMahon, if they, too, had tested positive.

“Why?” McMahon queried.

“They were with me,” The Sheik said with a childlike innocence.

A DANGER TO HIMSELF

By the early 2000s, The Sheik was desperate to find new ways to subsidize his drug habit. Sometimes, he’d sit in the lobby of the Ramada Inn near Atlanta’s Hartsfield Airport, a replica championship belt draped over his shoulder and a stack of 8-inch-by-10-inch photos on his lap. Inevitably, he’d be recognized and start selling his autographed photos for $10 apiece.

Then, The Sheik and his closest friend—a fellow suburban grandfather with no connection to the wrestling business—would drive into the ‘hood, trading the cash for crack. In some cases, The Sheik managed to barter, exchanging an autographed photo instead.

Yet, when Marissa died, The Sheik made a sincere effort to repair his family. “He stopped drugs cold turkey,” Tanya says. “Unfortunately, we were all in a very weak place, and he went back.”

Other attempts at sobriety followed. In 2005, the family signed papers alleging that The Sheik was a danger to himself and others, forcing him into rehab. But an employee at the facility snuck in an eight ball of cocaine.

“That’s the way it always was,” Tanya says. “People were taken by his celebrity, and they wanted him to like them. When the cops would arrest him, they’d drive him home instead of bringing him to jail. Every time we’d try to help him, he’d charm these fans, and they’d push back against us.”

SOMEONE DIFFERENT

If the former Caryl Peterson could redo her life, she’d encourage her husband to pursue “any other profession” but the wrestling business.

“There’s insecurity,” she contends. “It robs you of your family. The person you love is far away, hurting his body. And when it’s over, at least in his era, you’re not prepared for any other line of work. There are so many injuries, you can’t even do manual labor. And who is left to pick up the pieces? The wife, like always.”

Yet, at the time of their 1975 wedding, the preliminary wrestler then known as Khosrow Vaziri—a clean-cut babyface, or fan favorite, with jet black hair, who came to the ring in a singlet adorned with Olympic rings—was a clear-headed gentleman who held open doors and bestowed compliments on his bride.

“He was someone different,” Caryl recounts.

Future tag team partner Volkoff remembers a young Vaziri asking for assistance with the letters he sent home to Caryl. “Back then, he was a lot like me,” says Volkoff, a performer who stood out for the temperate, frugal life he lived on the road, “ripped like steel. He watched what he ate. Maybe he was drinking, but I didn’t see it.”

Once he was married, Vaziri wanted to ensure that he could support his family. So when Gagne’s wife, Mary, suggested that he rename himself The Iron Sheik, the former AAU champion was receptive to the gimmick.

After the 1979 hostage crisis, the powerful foreigner could enflame audiences simply by passing through the curtain, wearing Thief of Baghdad-style boots that curled upward. In his hand was an Iranian flag on which future WWE announcer Jerry "The King" Lawler had airbrushed the likeness of the Ayatollah.

As McMahon began the expansion of his northeastern-based territory, swallowing up other regional promotions, The Sheik played a critical role, dethroning Bob Backlund for the World Wrestling Federation championship on Dec. 26, 1983.

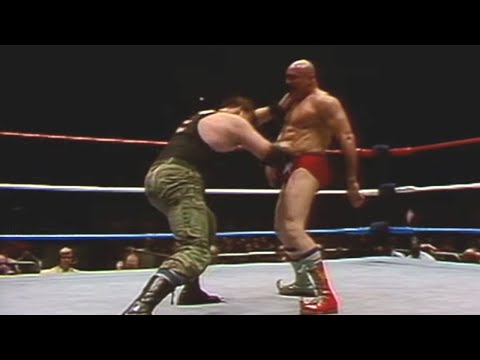

Even after he dropped the title to Hulk Hogan a month later, The Sheik was good enough to be a main eventer, bending foes backward on the mat with his camel clutch or bashing them with a loaded boot. His most memorable encounter: a bloody 1984 Boot Camp Match with all-American Sgt. Slaughter.

Outside the arena, The Sheik considered Slaughter one of his closest friends. Even so, Khosrow Vaziri was starting to forget that he wasn’t really The Iron Sheik.

BEYOND EMBARRASSMENT

“I have always preached to my husband to leave The Iron Sheik character out back,” says Caryl, “and then, he could come into the house.”

From Tanya’s point of view, though, it was exhilarating to have The Iron Sheik for a father.

In the supermarket, The Sheik lectured shoppers on their eating habits, calling strangers obese and even taking food out of their carts.

At the health club, he’d refuse to let members sit in the sauna, forcing them to do calisthenics in the heat. “He’d make people throw up,” Tanya says. “One guy had to do calisthenics until he passed out.

“I watched his wedding ring roll off his finger.”

During a retreat to Buford Dam in northern Georgia, while the rest of the family picnicked on the shore, The Sheik immersed himself in the strong, freezing currents. Remembers Tanya, “People were walking by and going, ‘Who’s that nut taking a shower in the ice cold water?’ Then, they’d look a little closer and say, ‘Oh my God, it’s The Iron Sheik.’”

Although The Sheik seemed beyond embarrassment, he displayed genuine contrition in 1987, after he and "Hacksaw" Jim Duggan were arrested on the New Jersey Turnpike en route to a show. Police found less than an ounce of marijuana on Duggan, and an eight ball of cocaine in The Sheik’s bag.

Up until this point, wrestlers and promoters had lived by a credo to protect the business. In certain territories, babyfaces and heels were banned from driving together. More than one promoter warned his performers never to lose a bar fight; doing so, it was reasoned, would make the talent look fallible to paying customers.

Now, with the World Wrestling Federation experiencing unprecedented popularity, the story of the in-ring enemies partying together before their match suggested that the whole thing was a “work,” or a con.

During a dressing-room meeting, McMahon literally pounded on a podium and declared that the pair had disgraced the industry and would never work for him again (each was eventually re-hired). After seeing the story on the front page of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Caryl kept her girls out of school for three days.

“The mistake cause me a lot of problem,” reflects The Sheik.

WACK PACKER

Interestingly, The Sheik’s descent into drug addiction coincided with another series of events in his life.

In 2002, an indie wrestler arranged for The Sheik to appear on The Jerry Springer Show. “His gimmick worked outside a wrestling arena,” notes The Sheik’s current manager and “nephew,” Jian Magen, 34. “He never had to do another camel clutch again, and the people still wanted to see him.”

Four years later, Jian and his twin brother, Page, encouraged The Sheik to make a YouTube video about Michael “Kramer” Richards’ racist remarks during a comedy show.

The moment the camera was on, The Sheik went into character, but, without the filter mandated by WWE, his angry monologue was peppered with obscenities. Howard Stern began playing the former wrestler’s rants on his radio show, then invited The Sheik to become a member of the program’s “Wack Pack.”

Fueled by drugs and emotional destitution, The Sheik blurted out shocking diatribes, threatening to sodomize old wrestling rivals like Hulk Hogan and B. Brian Blair, referring to Randy “Macho Man” Savage as a “cheap Jew” and using a variety of unsubstantiated homophobic slurs to describe the Ultimate Warrior.

“The strange thing is that he actually loves gays and loves Jews,” insists Jian. “It’s almost a parody of a slur because, as a wrestling heel, The Sheik was always trying to raise heat. It never meant anything when it came out of his mouth.”

WHO’S CURSING IN FARSI?

Jian Magen was three when he realized that his family was connected to the brawny man with the bald head and handlebar mustache on television.

“My mother walked into the room and yelled, ‘Who’s screaming those bad words in Farsi? Change the channel.’ Then, she looked at the screen and actually dropped a bowl.

“'It’s Khosrow.'”

The Magens’ father, Bijan, a Persian Jew, had been a table tennis champion in Iran, practicing at the same complex where The Sheik trained as a wrestler.

In Toronto, Bijan was in the carpet and flooring business. Now, he sent word to The Sheik that, whenever he was in town, he was invited to take sanctuary in the Magen home. He regularly turned up for Persian meals there—usually with Volkoff, Big John Studd, Jim “The Anvil” Neidhart or the Magnificent Muraco.

Almost instantly, the Magen brothers considered The Sheik their uncle. “Despite his gimmick, despite everything else, we always knew The Sheik as the kind, considerate, sincere man he really is,” Jian says.

Eventually, the twins became party promoters, flying The Sheik up to Toronto for wrestling-themed events. But shortly after Marissa’s death, Jian noticed something that upset him:

“I actually smelled it first. We were backstage somewhere, and I caught him doing crack with a fan.”

There were phone calls back and forth with Tanya and Caryl. Yet, no one could stop The Sheik’s downward spiral. In 2005, he came to Ontario for some type of card convention. The twins were working at a bar mitzvah when the promoter called them to say that the former champion was demanding to see “his nephews” immediately.

“I could hear screaming in the background,” Jian says. “And the guy is saying, ‘He just hit me. He just slapped me.’

“Eventually, I agree to leave the bar mitzvah and meet The Sheik at a Holiday Inn. He calms down, the other promoter leaves and I go home.”

A half-hour later, though, the hotel phoned the brothers. “He’s ranting in the hotel, and the cops are coming. The cops are kind of fans, and they don’t want to lock him up. So they take him to a shelter at a church. Now, we hear that The Sheik is screaming at the homeless people, keeping everybody awake, and he’s really sick.”

When the Magens next saw The Sheik, he was in the hospital. According to the doctors, he’d suffered a heart attack. Over a four-day period, he detoxed. But when he looked at the world with a lucid mind, his thoughts would be flooded by details of his daughter’s murder.

Once again, he turned to drugs, characterizing the substances he abused as his “medicine.”

'YOU KICKED IT, MAN'

In 2007, while The Sheik was out of town, Caryl exercised the only option left. “I up and moved out on him,” she says. “I could no longer beg him to quit. We had lost our daughter. We were all sad and depressed. But enough was enough.”

The couple lived apart for two years, until The Sheik agreed to an ultimatum: He had to sever his ties to his closest friend, the man who'd accompany him to the inner city to purchase drugs. “It was a painful thing for him because they’d really become best friends,” Tanya says. “But he cared about my mother more.”

Adrift, without a running buddy, The Sheik finally took sobriety seriously. Although he still drinks beer, he claims that he hasn’t ingested any form of cocaine in four years. “It was pretty hard,” he says. “But I don’t miss it anymore.”

In interviews, The Sheik is open about his struggles. But occasionally, he’s angered by the overemphasis on those problems. “They’re going to think I’m like Elvis or Michael Jackson,” he said after a recent article.

“No,” responded Jian, who’s been working on a documentary about his idol for the past six years. “Those guys died. You kicked it, man.”

TWITTER STAR

As The Sheik was cleaning up, the Magens brought him to a Twitter convention in Los Angeles. After gaining a cult following through Stern, The Sheik was interested in finding a way to communicate with, and entertain, the masses. Sitting on a panel, in a red-and-white striped kaffiyeh, The Sheik was asked about old rival Hulk Hogan.

“F*** Hulk Hogan,” The Sheik shouted to wild applause.

If that was all it took to make his fans happy, The Sheik decided to tweet (@the_ironsheik) on an almost daily basis—Jian admits that either the Magens or the wrestler’s immediate family assist in the process. He currently has more than 320,000 followers, many of whom re-tweet The Sheik’s messages.

(Beware: Some tweets NSFW)

“Paula Deen the dumbest bitch in the world.”

“Kim K ass bigger than Grand Canyon.”

“I am going to beat the f*** out of (Justin Bieber) and put his mother in the camel clutch.”

“He understands his audience,” Caryl says. “At a comedy show or a wrestling show, he knows what the people came to see. But we don’t have to deal with that side of him anymore.”

TIMELESS

“A pencil has eraser because it make mistake.”

Hossein Khosrow Vaziri rests on his cane, lecturing his grandchildren, Niko, two, seven-year-old Vahra—named for his grandmother—and Marissa, eight. It’s a sermon he gave his own children about not judging themselves too harshly. But as Tanya listens, she knows that her father is also talking about himself.

When Tanya named her oldest child after her late sister, both her parents and husband were uncomfortable, fearing that every time they saw the little girl, they’d remember her aunt’s violent ending. But now, no one regrets the choice, and The Sheik has grown particularly close to Marissa.

“It almost feels like a reincarnation,” Tanya says. “Even though her real middle name is Ariana, both of my parents call her Marissa Jeanne, just like my sister.”

A few short years ago, no one in the family ever imagined that both Marissa’s memory and The Sheik’s quality of life could be restored to this degree.

“He taps into a time people remember fondly in their lives,” Jian says. “He still fascinates. He still has relevance.”

And, after years of provoking hatred in wrestling fans and exasperation in his family, he’s—literally and figuratively—turned babyface.

Keith Elliot Greenberg was the only print reporter invited to The Iron Sheik’s room after he won the World Wrestling Federation championship in 1983.

Read 0 Comments

Download the app for comments Get the B/R app to join the conversation